So much so, that they then replay every previous scene in their head, looking for clues that they were too enthralled by the plot to notice. When the plot before the twist is boring or silly, the audience begins to notice clues and hints, destroying the total surprise of the twist.

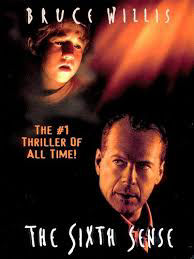

The Sixth Sense, excluding the incredibly twisty last ten minutes, is a family drama masquerading as a horror movie. Bruce Willis stars as Dr. Malcolm Crowe, a child psychologist whose marriage is deteriorating because of his complete consumption by his work. After a former patient, played by Donnie Wahlberg, breaks into his house and commits suicide in front of him, Dr. Crowe feels like he has failed at his life’s work and is desperate to help someone, making him even more distant from his wife, played by Olivia Williams. The child that he attempts to help is Cole Sear, played by Haley Joel Osment, giving, perhaps, the most competent and compelling performance from a child actor to ever grace the silver screen. Cole is parented by his single mother, played by Toni Collette, who struggles to handle Cole and his behavioral issues.

It is revealed quickly that Cole sees dead people, providing subtle, but extremely effective horror throughout the film. Cole is just as scared as we are by the ghosts, and most of the movie centers around Dr. Crowe’s attempts to help him coexist peacefully with them.

This would all make for a terrifying and lovely movie, but then comes the reveal: Dr. Crowe is dead. Without this reveal, The Sixth Sense is a perfectly enjoyable viewing experience, but with the edition of a twist, it is iconic.

Writers, especially in the horror genre, have been using plot twists for hundreds of years. One of its earliest uses in film is in the German expressionist movie, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, from 1920, where the ending reveals that main character is insane, and the whole plot has taken place in an asylum. The Sixth Sense is considered to be the film that really popularized the twist device. Some feel that 1995’s The Usual Suspects is more responsible, but either way, the early 2000s was a haven for twisty movies, most of which did not measure up to their predecessors.

However, twists have been around for as long as stories have. The plot twist has stuck around so long because it is a trope that is very effective at eliciting a strong reaction from the audience. The worst response to any piece of art is indifference, and in a market as saturated as the movie industry, having a scary or moving or funny or thoughtful story is not always enough to get people excited. A good surprise, however, is sure to make us feel, whether it be positively or not.

Many people see the use of a trope like the plot twist as a crutch for the writer, but I believe that writing an original and effective twist is incredibly hard to pull off. Twists often rely on the audience’s biases and preconceptions. Shyamalan, a movie lover himself, knows that viewers have become accustomed to what I will call movie logic. Movies rely on the understanding of the viewer that the character’s lives go on off screen. We may not see the main character go to the bathroom, but we assume that they do because that is just what humans do. Shyamalan uses those assumptions against us, and leaves holes in the narrative, that upon a second viewing are obvious, but are filled in by movie logic the first time around.

For example, after Dr. Crowe first meets with Cole, it cuts to a scene of Dr. Crowe with Cole’s mother, Lynn. We assume that we have stumbled in towards the end of their conversation as Lynn just looks dejected and Dr. Crowe just looks back apologetically. The scene is just long enough to make it not suspicious and just short enough to make us believe that Dr. Crowe has met Cole’s mom, and is not treating him without the consent of his guardian.

In another similar scene, Dr. Crowe shows up to a restaurant for dinner with his wife. We assume that he is late because she has already asked for the check and seems upset. He apologizes and she ignores him. We assume that she is just mad at him. She then takes off her wedding ring and whispers happy anniversary before leaving. We assume that Dr. Crowe is a terrible husband and that she is leaving him, but after discovering the twist, it is clear that she is grieving him and trying to move on.

Other nuanced details are scattered around the film as clues to the twist that are not clear until you are looking for them, like how we never actually see Dr. Crowe eat or move anything. Movie logic tells us not to worry, he is eating off screen and there was no narrative reason for him to move anything, right?

Shyamalan’s deception leads to the big idea of the film: assumptions will usually lead you astray. The twist makes people, as they leave the theatre or close their laptops, think about how their expectations led them to miss the truth while it was hidden in plain sight. Making a movie that gets that audience to do that kind of introspection is no easy feat, and Shyamalan's success with it in this movie has cast a long shadow. Each of his movies since have struggled to live up to The Sixth Sense’s promise, that M. Night Shyamalan would be the star director and twist-maker of his time.